How to deal with your political angst

Volunteer. And I mean that in the more traditional sense: give time to your neighbors and to organizations doing good work.

Given the writing I do in and around politics, for people I know socially, I’ve occasionally become their political therapist—what’s actually worrying vs. what’s just a sensationalist headline, etc.

Needless to say, it has been a rough month. There is a lot to be worried about.

In this informal, unremunerated role as a political therapist, the question I’ve been getting most: “What can I be doing?”1

Having thought about this a bunch, my answer: volunteer. And I don’t mean volunteer by knocking on doors for political candidates—that has its time and place. I mean helping neighbors and volunteering for organizations that do good work.

Why?

The most obvious: it’s important and does good. If you are worried about the impact that our government is having, as I am, this is a pretty direct way to counteract that. This isn’t resigning yourself to whatever is happening in Washington; to volunteer is to take a stand.

Volunteering makes you measurably happier and measurably more optimistic. In a political landscape where there isn’t a lot to feel great about, it will literally make you feel better.

It’s measurably good for your health.

In a moment where people feel lonelier and more disconnected than ever, it’s a good way to build community and make friends.

Information on how to volunteer is at the bottom of this email.

The data on volunteering and charitable giving

The Census Bureau and AmeriCorps, I was surprised to learn, track how often Americans over the age of 16 say that they volunteer.2

54% say they informally volunteer (at least once per year): helping a neighbor with groceries, offering free childcare, etc.

28% say they formally volunteer through an organization (at least once per year).

Volunteering peaked just after 9/11.3 It’s been declining since then, and although it’s recovered from lows during the pandemic, rates are roughly flat over the last eight years or so.

Studies very consistently find that conservatives are more charitable than liberals,4 a finding that should give liberals pause—and encourage them to find ways to get involved and volunteer.

Volunteering makes you happier, healthier, and live longer

People are happier when they volunteer more; that’s been reasonably well documented for a while now. The challenge, of course, is assessing causality: are people happier because they volunteer more? Or do they volunteer more because they’re happier?

It turns out that volunteering—causally!—makes you happier,5 according to a 20-year-long longitudinal study.6 People who volunteer are also more optimistic.

The benefits extend to physical health too, and those who volunteer live longer, were less likely to develop high blood pressure, have decreased pain levels, and experience myriad other health benefits.

Volunteering builds community and makes people less lonely

Utah—which as I’ve written about, is a real outlier when it comes to all sorts of community-oriented outcomes—has by far the highest rates of volunteering of any state in the country.

On the flipside, Nevadans help their neighbors at the lowest rate in the country. What’s also notable about Nevada: only 27.2% of Nevadans were born in Nevada, by far the lowest of any state.7

I’ve written about the crisis of loneliness before—it is one of the most pressing issues of our time.8 And it is no accident that Nevada is the loneliest state in the country, at least by one measure.9 Obviously, lower rates of volunteerism aren’t the sole reason for that, but a lack of community—which ties into that lack of volunteerism—is a clear contributing factor.

It turns out that volunteering is a great way to meet people10 who share your interests, values, and desire to do good. And sure enough, people who volunteer are less lonely: volunteers are 29% less likely to say that they’re disconnected from their friends.

Volunteering does matter

This comes from a really terrific article in Vox by Rachel Cohen:

Last fall, a reader asked me what they could really do, as one person, to aid people living on the streets. “I often feel helpless to enact change,” they wrote…

My mind immediately went to systemic solutions, like voting for candidates who prioritize building more housing, or supporting efforts to loosen zoning codes.

But when I called experts, their answers surprised me. Some of our ideas overlapped, but many of their suggestions were ones I had admittedly not entertained: passing out socks or hand-warmers, donating items like sleeping bags to local shelters, or giving office supplies and bus passes to nonprofits serving unhoused people.

Cohen’s article—that for too many of us, charitable beliefs are a proper substitute for charitable giving and charitable deeds—is worth reading.

I’m not saying that agitating for policy change is unimportant; it’s very important. But giving back has an immediate and direct impact in a way that even good policy cannot. The overwhelming majority of nonprofit leaders say that volunteers improve the quality of their services and programs.

Americans donate five billion hours of their time per year—the equivalent of $167 billion in value. It may not be enough, but that’s pretty extraordinary.

How to volunteer

The simple answer: what are the causes you care about most? Reach out to those organizations; that survey I just mentioned (that found that most nonprofit leaders rely on volunteers) also say that they have far too few.

If you need help figuring out where to go, VolunteerMatch is a great place to start. Beyond that:

For those of you in St. Louis, the United Way Volunteer Center is a good resource. I thought r/StLouis had two good threads too: this Reddit thread and this separate Reddit thread.

For those of you elsewhere, reach out to local organizations you know and care about. This AP article has some good guidance. And as above, searching your city’s local subreddit isn’t a bad place to look either.

I’ll speak for myself: I used to volunteer more and then fell off during the pandemic. I’m not alone in that regard, but at this point it’s a flimsy excuse—the pandemic started five years ago now.11

There’s only so much I can do to change what’s happening in national politics. But this is something that can make a difference and make all of us feel better about the world and our communities.

I cannot think of a more worthy use of your time, or mine.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing.)

For press inquiries, please contact press@ben-samuels.com.

Often with an expletive thrown in there, I’ll note.

The polling methodology was surprisingly difficult to track down. (I’ll tell you why I cared so much about the methodology in a moment.) I went from USAFacts.org to this AmeriCorps page to a Census Bureau page that directed me straight back to an AmeriCorps PDF where I found this footnote: “For methodological details, please see the full technical documentation and frequently asked questions about the CEV at data.americorps.gov.” It all started feeling a little bit like this xkcd:

But hey, the data must be in that FAQ…right? Nope. The AmeriCorps’ data page doesn’t even have an FAQ! Down the rabbit hole I went. Eventually, after way more searching than it warranted, I finally found the methodology page. (Note that opening this link will automatically download a 224-page document from AmeriCorps.)

Why go through 45 minutes of trouble to find this? Because I was curious whether their data was observed or self-reported. Here’s the answer, on p. 9: “The September 2023 Civic Engagement and Volunteering Supplement attempted to obtain self-responses from household members 16 years old and over.”

It matters that people self-reported because I think people likely inflate the amount of volunteering they do for the same reason we inflate how many times per week we floss to our dentists: it’s the answer we know we should give, even if it’s not totally true.

There isn’t any better data out there, but I bring all of this up to say:

All of this data should probably be taken with a grain of salt. With that said, if questions are consistently asked over time, it’s probably still a good measure of change.

I’ve complained about government data before, and I’m sure I will again. With that said: the last time I complained about government data, I asked them to fix it and they did so within about 24 hours. So that was impressive and nice to see.

This data was first tracked, in earnest, going back to the ’70s, so the spike in volunteering around 9/11 is the highest in at least the last 50 years or so.

Some of this, though not all of it, may be attributable to things like religiosity, and therefore how much people donate to religious causes (including tithing). But that doesn’t account for everything.

It should also be noted, according to one recent study: “We find that stronger religiosity increases volunteering toward individuals in their faith group (in-group). However, conservative beliefs reduce volunteering toward causes outside of an individual’s faith community (out-group).”

So it’s not without its issues, clearly, but I’m comfortable nonetheless saying that more volunteering is better than less volunteering, even with these caveats.

There are different theories for why that is (one involving the reward pathway in your brain being triggered when you do good deeds), but doing something good that makes you feel happier is a compelling combo.

More accurately, it finds that people who volunteer tend to be happier to begin with and become even happier when they volunteer. Even still, that’s pretty cool. (h/t to The Washington Post for referring me to this study from this article.)

The New York Times ran an analysis on this back in 2014, but once again, pulling more recent data was surprisingly difficult—I had to manually work through a pretty-challengingly-formatted Census spreadsheet to get this.

By the way, if you’re curious:

Louisiana has the highest percentage of its residents born in-state: 77%.

65% of Missourians were born in Missouri, the 14th-highest of any state in the country.

57% of Americans were born in the state they live in today.

So Nevada is way an outlier on all of this.

The percentage of people born in-state who live in-state is a highly inexact way of getting at whether someone has community or not. Lots of transplants build incredible communities, and of course lots of people who live in their hometowns are lonely.

But it’s one of the easier ways to look at this, and I don’t necessarily think it’s an accident that Nevada is at the bottom of both.

How you define loneliness is pretty challenging, so this is just one way of looking at it. Different people come to different conclusions by defining loneliness in different ways and weighting different measures. Some, of course, just make it up entirely. But the definition I used was backed by at least some data.

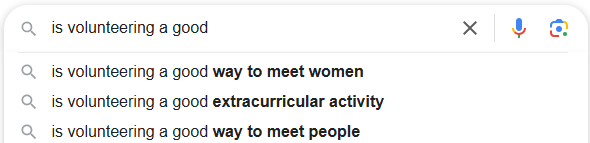

Just to be clear: this is about meeting friends, despite what Google thinks you have in mind when you’re asking about meeting people while volunteering:

(By the way, if you’re wondering, the internet seems to think… yeah, maybe it is.)

Fourth graders at the beginning of the pandemic are in high school now. And that definitely makes me feel old… It’s wild that it’s been five years—it still messes with my sense of time.