The vanishing voices of WWII veterans

The last World War II veterans are in their late 90s and 100s. They shaped the world we live in today. But their perspectives are fast disappearing.

When I was in fifth grade, after a unit on U.S. history, Mr. Greco gave us an assignment: interview a World War II veteran, and report back to the class with what we’d learned.

This was in 2002. Back then, that wasn’t particularly challenging: a lot of us had grandfathers who fought in WWII, and people who didn’t surely had a neighbor or a family friend who did. Most veterans were in their 70s or 80s.

Today, of course, is a different story. The youngest WWII veterans are 97.1

It feels like every few weeks, you read a new story about a “last surviving” WWII veteran: the last of the Band of Brothers2 or the last Doolittle Raider or the last USS Arizona survivor, for instance.3 Within the next decade or so, the final World War II veteran will have died.4

We are fast losing our tether to the people who fought to protect the world from fascism and tyranny. We’re losing the people who understand the dangers of isolationism, and why international collaboration is good.

Understanding that maybe helps us do something about it.

World War II veterans were ubiquitous for generations

Until recently, this wasn’t an issue.

16.4 million Americans served during WWII, about 12% of the country’s population at the time—an astonishingly high number.5 And that still understates the impact that WWII veterans would have for decades to come.

For generations, they were present in all walks of life—at our businesses, in our communities, and at our schools. They were also very present in American politics.

WWII veterans in elected office

Even against the baseline of enormous participation in World War II, veterans were disproportionately well represented in politics for decades.6

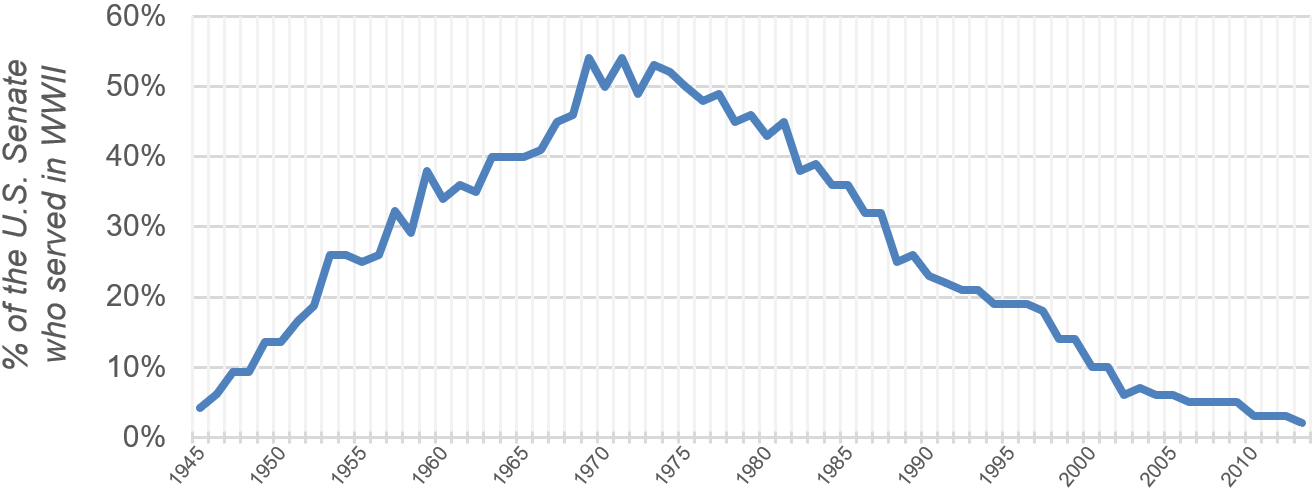

From 1953 to 1993, every single President of the United States was a WWII veteran.7 And at its peak in the late ’60s and early ’70s, 54% of U.S. Senators had served in WWII.8

Even 40 years after that peak, there were still Senators who’d served in the War,9 building seniority and expertise and cache such that even as their number dwindled, they continued to have an outsized impact on legislating and public discourse.

Why talk about this now?

The Greatest Generation is valorized,10 at times in ways that sweep under the rug the challenges of wartime and post-War America. Rising prosperity in the late ’40s and ’50s often excluded both women and minorities, for instance, despite their contributions to the war effort.

The goal here is not to deify World War II veterans.11 Rather, it’s important to acknowledge that a group of people came together to win a war whose set of goals (non-exhaustively) included:

Defeating tyranny.

Fighting for the rights of minorities and the discriminated against.

Fighting for self-determination and democracy.

It’s no surprise, then, that in Congress, support for NATO, for international trade, and for the rights of refugees had been strong for decades.

That’s obviously quite different now. Donald Trump is threatening to cut ties to NATO, blow up international trade, and block refugees from coming to the United States.

A generation ago, lawmakers would’ve (rightly) seen all of this as a threat to world peace and stability. They’d seen and experienced what happens when you dive head-first into isolationism.

But those people are mostly gone. Without their collective memory, wisdom, and experience, we are squarely living in the post-post-War era.

Younger people don’t believe in a lot of what America has stood for since 1945

Older voters lean significantly more Republican than younger ones.12 So it’s noteworthy that older people are much more aligned with a lot of what we fought for in WWII—issues that aren’t in line with today’s Republican Party—than younger people are.

Older people, for instance, are more supportive of NATO, more supportive of Ukraine, and less supportive of Russia than younger people. Most surprisingly, perhaps, people who are 65+ are more supportive of refugee resettlement than people under 30:

But all this goes even further. Younger people are far likelier to see democracy as no better than a dictatorship—or worse yet, to agree that dictatorship can be good in some circumstances:

All of this paints an alarming picture of how younger people view the world:

Less supportive of democracy.

More supportive of isolationist policies.

Less supportive of refugees.

Against the framing of World War II veterans, this makes some sense. Older adults were much likelier to have grown up around—and in many cases, to have been raised by—people who fought in and lived through WWII. They may not have experienced the worst of a pre-War world themselves, but they heard it first-hand.

As the last of the WWII veterans die, how do we protect what they fought for?

Father Time is undefeated—there’s nothing we can do to fully bring these perspectives back. What was once a first-hand account is becoming a second- or a third-hand account—or people aren’t learning about this at all.

Preserving the memories of people who served during World War II—and, in the years to come, the Korean War, the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, etc.—is important and worthwhile.

Here’s what you can do:

Interview the people in your life. I recorded my grandfather talking about his service as a Marine during WWII, and have done other similar interviews too. It requires some planning, but anyone with a phone and 30 minutes can accomplish a remarkable amount.13

As education risks becoming more partisan and more explicitly political, stand up for education14 that helps people understand what we were fighting for during World War II, and what we’ve been fighting for in the decades since.

In a world that’s becoming increasingly inhospitable to them, support refugees by giving to organizations like HIAS and the International Rescue Committee.

Why I care

World War II is personal to me. I’m named after two WWII veterans, my grandfather and my great-grandfather. I had family murdered in the Holocaust.15

But even beyond that, I believe in what we fought for during WWII. I believe we have a moral obligation to help refugees; I believe we have a moral obligation to promote peace in the world; I believe that multiculturalism, here and abroad, is worth defending.

We’ve lost most of the voices who can best, and most personally, argue for why all of that matters.

The one thing you can immediately do is talk to—and record—people in your life. Putting any politics aside: my grandfather died a few years after I interviewed him, and I’m enormously glad now that I did.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. (If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing.)

I do not receive direct replies to this email. For press inquiries, please contact press@ben-samuels.com.

Assuming they were 18 in 1945, they were born in 1927, which means that they’re 97 today. There are a handful who were younger—people lied about their age to enlist—but surely everyone is in their mid-90s or older.

The last Band of Brothers officer was Edward Shames, who died in 2021. His obituary included the incredible detail that at the end of the War, he stole a bottle of cognac marked “for the Führer’s use only” which he opened and consumed at his son’s bar mitzvah. Just a top-tier example of f***-you karmic justice.

Since I started drafting this about a week ago, the NYT wrote another one of these articles. It is, unfortunately, happening all the time.

The last World War I combat veteran died in 2011 at 110 years old. If you assume some math similar to that, the last WWII veteran will die sometime in the late 2030s. But of course, the vast majority are already gone.

After the 80th anniversary of D-Day a few months ago, a lot of the press coverage made reference to the fact that this would likely be the final major commemoration with any survivors present. Here are some quick examples of that.

Especially when you consider that children, older people, and most women didn’t serve—at least not formally in the Armed Forces.

Some of this has to do with the fact that positions of power were largely closed off to women. And while there were women who served in the military, of course, they did not do so at the same rate. (And often contributed to the war effort in other ways.)

Dwight Eisenhower, elected in 1952, became President because of his service during WWII. Other Presidents had varying levels of involvement—Jimmy Carter’s was very loose, for example, as he was a student at the Naval Academy towards the end of the War—but it’s still a remarkable run.

The data on the official U.S. Senate website is, frustratingly, not totally accurate. Henry Bellmon, for example, did not serve from 1942–54 as the website says. (In fact, he would’ve been Constitutionally ineligible to serve for part of that window, as he wasn’t 30 yet.) He instead served from 1969–81. I corrected this specific error but otherwise did the best that I could without going line-by-line to fact-check this data. (This was necessary to preserve my sanity.) Ahh, the joys of government data.

Update: I got them to fix this error! And they did it pretty quickly too. Kudos to the Senate staff.

Wisconsin State Senator Fred Risser, who retired in 2021, was the last elected official in the U.S. to have served in WWII. Risser had an astonishingly long career in elected office: he was in the Wisconsin State Assembly for six years starting in 1957, and then he served in the Wisconsin State Senate from 1962 through 2021.

I mean, that generation’s name is literally “the Greatest Generation,” which is pretty good evidence of said valorization.

There were plenty of remarkable people who served during WWII, and plenty of bad ones too. Albert Sabin and Cesar Chavez were WWII veterans; so were George Wallace and L. Ron Hubbard. (L. Ron Hubbard may have taken that deification a bit too literally.)

Younger voters moved to the right in this most recent election—especially younger men. But they’re still meaningfully to the left of older voters.

As you can tell from the interview that I did, it’s hardly professional-grade work. And that’s just fine.

What does this mean, concretely? A lot of it is critical but isn’t glamorous: vote; volunteer at schools; run for school board; call your local and state representatives (who have much more say on education than anyone federally); be aware of what’s happening at schools in your area. In St. Louis, a lot of the most troubling school board candidates lost back in April, so there is positive momentum here—but the elections had turnouts below 20%, meaning that any individual’s involvement goes a lot further.

In my extended family, those ties run even deeper—like they do for a lot of Americans. I had a cousin who was killed in Normandy three weeks after D-Day, and a cousin who died, decades later, with the crippling effects of polio he contracted during the War.