Panic! Everything's bad! Give me money!!

That's the formula for online political fundraising. Campaigns send out lots of emails with little regard for how it damages our political system.

If you’ve ever gotten a political fundraising email, you’ll recognize that kind of subject line.

Having been a candidate for Congress a few years ago, I got to see firsthand how text and email fundraising works. It’s seedy, bad for our political system, and involves more lying and predatory behavior than most people realize.

At the bottom of this email, I’ve offered some thoughts on what you can do to protect yourselves and spare your inboxes.

Article summary:

Neither political party has the authority to tell candidates who they can send emails to, or what those emails can say. That leads to more chaotic and extreme messaging.

Your contact information is bought, sold, and traded between campaigns. In many cases, what campaigns send you is predatory and/or an outright lie.

There are steps you can take to protect your personal information and weaken this fundraising ecosystem, which is damaging to political discourse in America.

There’s no such thing as “The Democrats”

A line I heard once that I really like: people conceive of political parties as marching bands, but they’re really more like music festivals.

There’s not a conductor telling everyone how to act, what to say, and what not to say. There’s sort of an organizing committee via the DNC, but every candidate, advocacy group, and state party can communicate however they’d like. To complete the metaphor, everyone has their own stage.

Likewise, people think of “the Democrats” as a monolithic institution, with a master list of donors whose email addresses and phone numbers they give out. How it actually works: individual campaigns1 are free to message whoever they want, with any message they want, and with whatever frequency they want.

All of this sets up a tragedy of the commons. Every campaign is acting rationally by trying to communicate with (and raise money from) people as much as they possibly can. But politics suffers because people are spammed with frequent, low-quality, sensationalist, dishonest, and largely indistinguishable messages.

The same thing is happening on the Republican side, even if the messaging itself is different. Campaigns in both parties are guilty here.

How your information gets traded and sold

If you’ve ever wondered why it’s so hard to get your name off of email lists after you’ve donated money or even if you’ve just signed up to volunteer, here’s why.

For most campaigns, buried deep in their privacy agreement is the right to trade or sell your information however they want. They can sell their list of emails to generate more money for their campaign; they can buy them from other campaigns to try to raise money from new people.2

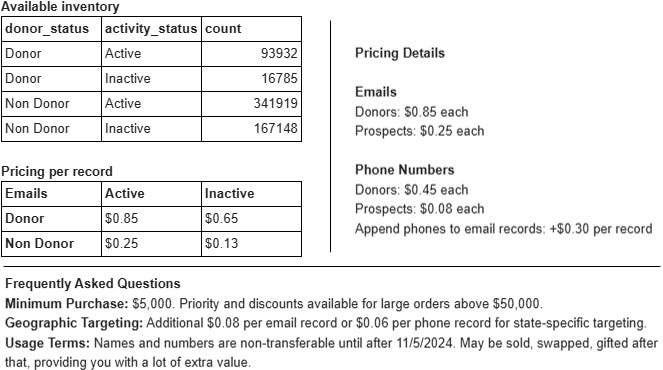

Here’s a screenshot of an email I got from a campaign that was interested in selling me their email addresses. It’s a pretty good reflection of how this stuff works.3

This campaign was offering me hundreds of thousands of email addresses and phone numbers. That’s a small fraction of the full political universe, where there’s contact info for tens of millions of people.

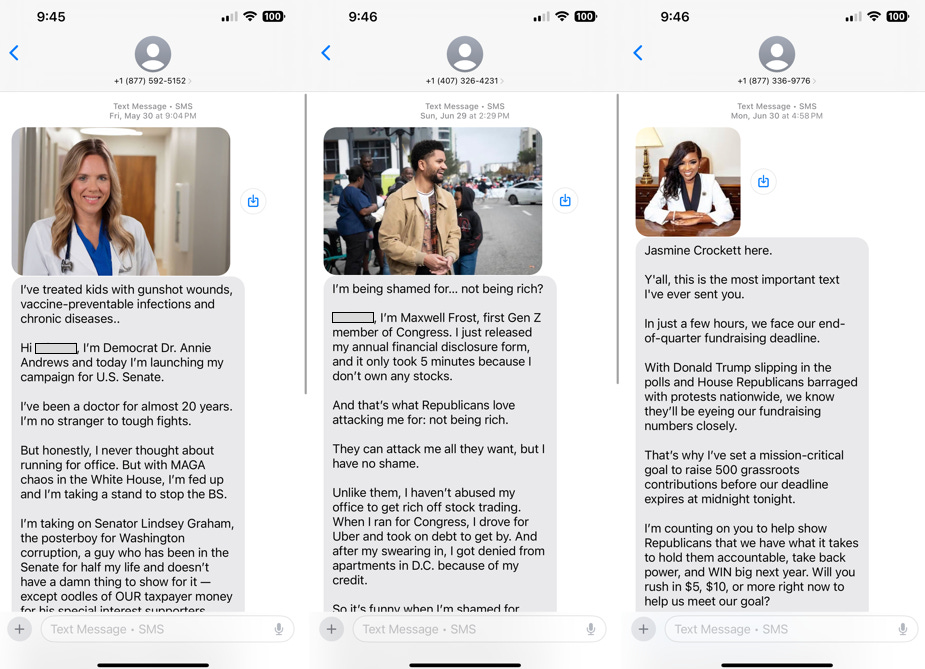

This is how your info gets passed around, and why you end up receiving text messages like these, from candidates and campaigns you’ve never heard of.

Text/email fundraising sets up totally misaligned incentives

Said another way, no one here has any incentive to be a good steward of either people’s contact information or of Democratic messaging generally.

Campaigns: Their goal is to raise as much money as possible, which means making their email lists as large as possible and hitting people up as frequently as possible. There’s no reason to be worried about burnout.

Email vendors: Most campaigns pay an outside firm to draft and send emails on their behalf. (Rarely are they written in-house, which is why every email looks and sounds so freaking similar.) Their incentive is to justify their fees, which means that they’re in the business of raising as much money as possible.

ActBlue: A lot of people think that ActBlue is part of the Democratic Party, but it’s not. They have their own incentives as an independent organization. They make money by taking 3.95% of every transaction on their platform; for context, that is meaningfully higher than standard credit card fees.4

Notably: email vendors and ActBlue have much stronger incentives to help campaigns raise money than to help campaigns win votes. This is, for a host of reasons, bad.

Why?

Messaging that helps people raise money is distinct from messaging that actually helps people win swing voters and, therefore, win elections.

It burns people out.

It’s borderline predatory.

It ends up funneling money to candidates with absolutely no shot of winning and/or who don’t need your money. Take the three text messages I shared above:

Annie Andrews is running in a crowded Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate seat in South Carolina, where any Democrat will very likely lose.

Maxwell Frost and Jasmine Crockett represent heavily Democratic seats (D+13 and D+25, respectively) and do not need your money.

Messaging in text/email fundraising is all terrible

The Archive of Political Emails is a wonderful resource, because it tells you what people are receiving in their inboxes. A couple of recent examples, first from Democrats and liberal groups:

And also from Republicans and conservative groups:

From Matt Gaetz: “EXONERATED.”5

You know what undecided voters care about? It’s not a MAGA super PAC and it’s not James Comey.

The three things that swing voters cared about most in the 2024 presidential election: the economy, immigration, and social security/Medicare.

These emails push extremism and actively make it harder to win more undecided voters. They advance a narrative that politics isn’t about helping people, but that it’s about tearing the other guy down. And reading these emails, maybe that narrative is right.

A lot of email fundraising is just a grift

Here are a few examples of that:

Have you ever gotten a matching pledge from a campaign? (“If you give $1, a donor will match your donation!”) Odds are extremely high that’s just a lie.

Fundraising tactics—from both political parties—have grown so deceptive that it’s literally bankrupting a lot of seniors. In the ’23-’24 cycle, nearly 20,000 people gave more than 100 ActBlue donations, which doesn’t look like responsible or rational behavior to me. One person in Washington state individually made more than 33,000 donations via ActBlue in that period.6

In 2022, Marcus Flowers ran for Congress against Marjorie Taylor Greene, raised more than $16 million, and lost by more than 30%. How? His emails effectively tricked people into thinking that donating to him was a good use of their money. (It wasn’t.)

The same thing happens on the Republican side; Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s opponent in 2020 raised nearly $10 million and lost the race by nearly 45%.

I wrote last time about how hard it is to contextualize large numbers, but: $10+ million is an extraordinarily large amount of money for an unwinnable U.S. House race. The average winner of a House race spent $2.79 million in 2022.7 Marcus Flowers raised and spent nearly 6× that.

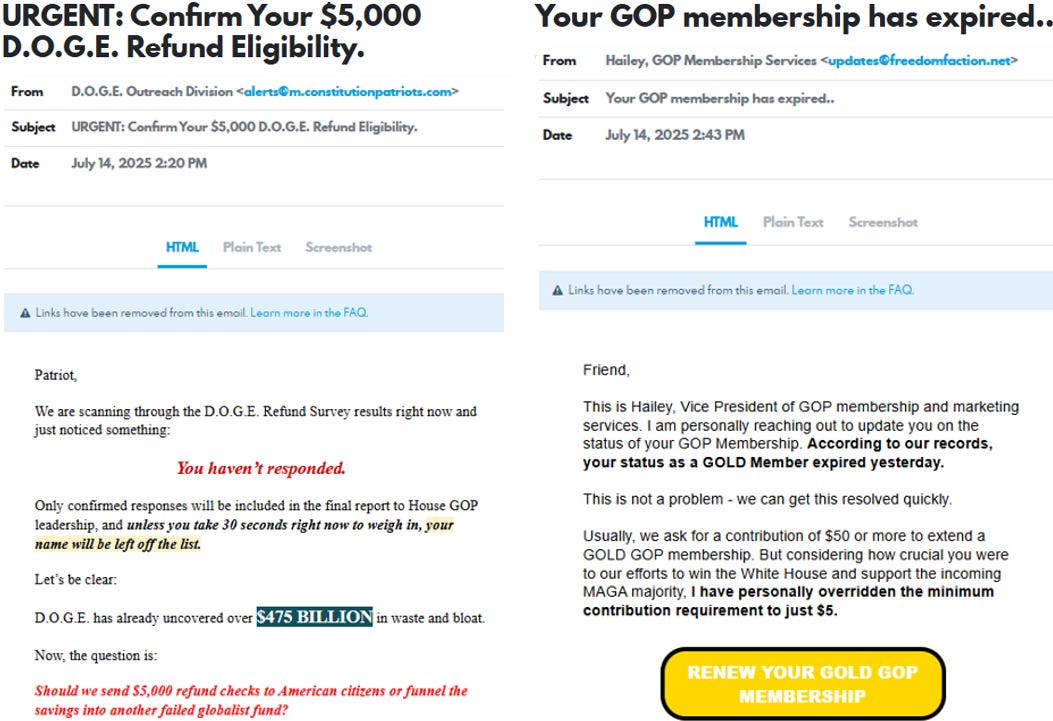

Beyond any of that, though, are all of the outright lies. No, JD Vance is not opening up a direct line of communication with you. A lot of emails are written to frighten people into action. For example:

The email on the left won’t get you a $5,000 refund check. It’s a fundraising email from Randy Fine, a Congressman in Florida.

And as for the email on the right, no, that’s not how party memberships work. It’s not even from the GOP—it’s from Nate Morris, who’s running for the U.S. Senate in Kentucky.

Both Morris and Fine are trying to bamboozle people into giving them money.

What can you do about all of this?

Because I was a candidate in ’22, I’ve been a beneficiary of this system; it’s brought me a lot more exposure than I’d ever otherwise have.

But I look back with regret; I’m embarrassed by emails sent in my name. It was a lot of the same crap that I’m annoyed about every time it lands in my inbox.

It took leaving that world to understand how bad and embarrassing the whole setup is. In hindsight, I would’ve rather raised a little bit less money and held onto a little more dignity.

Here are my thoughts on what you can do about this:

Be wary of any political email that you receive. The Vice President of the United States isn’t reaching out to you in a cold email or text. That matching pledge is probably made up. Approach emails with the same skepticism that you might any other cold call or cold email.

If you want to donate to candidates, if possible, don’t give money via ActBlue. Checks are fading away, but lots of Americans still write checks periodically, and that’s how I do my political giving. If you give money by check, campaigns keep more of your donation,8 and they don’t get your personal info.

Think about where your money is best deployed. Last year, I encouraged people to donate to candidates and causes where support would go the furthest.9 I’d love to see someone like Marjorie Taylor Greene lose, but she’s in an extremely Republican seat; it’s not going to happen. Money is better spent in more competitive races and districts.

If you must sign up for something online, use fake email addresses and cell phone numbers. You can get a fake email address on sites like these, and Google Voice works well for temporary phone numbers.

There’s already too much mistrust in politics. Emails and texts from both political parties make it worse, and we should do what we can to knock down a system that drives extremism and misinformation.

Feel free to share this post with someone who will find this interesting. If you’re reading this email because someone sent it to you, please consider subscribing.

This is a pretty broad term that could include candidates running for office, ballot measures, advocacy groups building support, etc.

“Swaps,” where a campaign trades emails with another campaign, are also quite common. (For example: a Candidate A in Virginia might give a Candidate B in Pennsylvania 1,000 email addresses for Pennsylvanians on their list, and in return, Candidate B would give 1,000 emails to Candidate A for people in Virginia. All of that would be totally cost neutral.)

To be really precise here: this is a screenshot of two separate emails that I received. I have combined them into one email for three different reasons:

To anonymize which campaign this came from.

To share more pertinent information.

To format it in a way that it works better with Substack’s interface.

Nothing about the text has been edited, nor does it change any of the substance. But I want to be clear that it’s not a verbatim email.

For context on what everything in that screenshot means:

Donors vs. non-donors/prospects: People who have donated money to this campaign vs. people who haven’t.

Active vs. inactive: Whether you’ve recently opened emails, clicked on links, etc.

It’s even higher than Square, which charges 2.9% per transaction (plus a fixed 30¢ per-transaction fee). I don’t know the exact structure of WinRed, the Republican equivalent of ActBlue, but I think it’s substantially the same.

Maybe this one is just wishful thinking on his part.

I’m not linking to sources here, because it includes people’s names and home addresses. Bulk data is available here from the Federal Elections Commission, which makes all of this sort of information public. I dusted off my long-dormant SQL knowledge to analyze 100+ million rows of data, which is my source for the stats above.

Right here in Missouri, Jess Piper raised nearly $300,000 for a State House race she lost by more than 50%. Like Marcus Flowers’ race, that’s an extraordinarily large amount of money for an unwinnable Missouri State House race.

Because ActBlue doesn’t take that 3.95% cut, which adds up over the course of a campaign that raises millions of dollars.

Relevant to all of this: I set up the ActBlue link in a way that campaigns didn’t get your email or cell information.